In 1964 The Dixie Cups, a female vocal trio from New Orleans, crooned out a cheerful version of “Chapel of Love” and knocked the Beatles from their number one spot on the pop charts. A year later, the trio released “lko lko,” a song first released in 1954 by James “Sugar Boy” Crawford as “Jock-A-Mo,” whose lyrics recount the meeting of two groups of Mardi Gras Indians. Since then, this song has been covered by artists from the Grateful Dead to Cyndi Lauper, and continues to move new generations with its infectious New Orleans rhythms. The career of The Dixie Cups, and their direct and indirect roles in carrying rhythm and blues (R&B) into mainstream consciousness, speaks to the enduring power of this music to transcend region and musical category and become a representative sound of the country.

The history of R&B and the breadth of what it encompasses—socially, commercially, and artistically—suggests that it is not monolithic. It tells a complex story of many strands and experiences. A distinctly African American music drawing from the deep tributaries of African American expressive culture, it is an amalgam of jump blues, big band swing, gospel, boogie, and blues that was initially developed during a thirty-year period that bridges the era of legally sanctioned racial segregation, international conflicts, and the struggle for civil rights. Its formal qualities, stylistic range, marketing and consumption trends, and worldwide currency today thus reflect not only the changing social and political landscapes of American race relations, but also urban life, culture, and popular entertainment in mainstream America.

The emergence of R&B as a music category reflects its simultaneous marginalization as a form of African American music and its centrality to the development of a wide repertoire of American popular music genres, most notably rock ’n’ roll. Three historical processes provide the framework for understanding the social and cultural contexts of the development of R&B: the migrations of African Americans to urban centers surrounding World War I and World War II, and the civil rights movement.

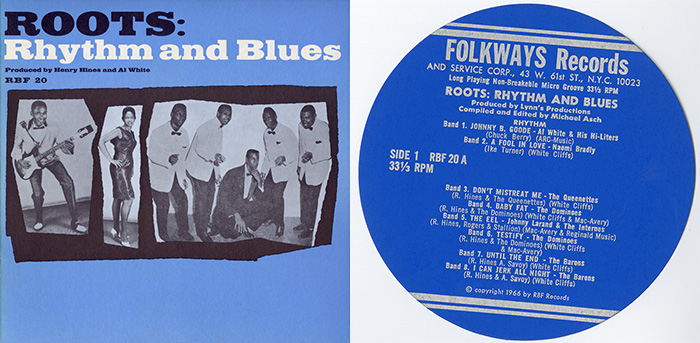

Hear “The Roots of Rhythm & Blues,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

The Great Migration

The development of R&B is closely intertwined with the growth of twentieth-century African American urban communities in cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Memphis, and Detroit, which were geographical anchors for how these processes played out across the country. The expansion of these urban communities took place during two periods of migration from Southern regions of the United States. The first, known as the Great Migration, occurred from 1916 to 1930, in response to the collapse of cotton agriculture due to boll weevil infestation and the demand for industrial workers in Northern cities during World War I. In concert with these shifts in population from rural to urban, many forms of African American expressive culture, especially music, were able to make transitions into urban environments and the marketplace.

African American residents in these urban areas confronted a range of discriminatory housing and employment practices, including restrictive covenants and segregation. Confined to such areas as Chicago’s South Side, Harlem in New York City, or near Central Avenue in Los Angeles, people in these residential neighborhoods represented all economic backgrounds and were served by a variety of business and commercial entertainment venues such as clubs, lounges, and theaters. A majority of the theaters were owned and operated as White businesses, requiring African American performers to secure bookings on the limited Theater Owners’ Booking Association circuit.

It was during this period that large national organizations working to support the social and political concerns of African Americans—such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909), the National Urban League (1910), and later, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (1925)—advocated for institutional change on a range of issues from voting rights to labor. As communities coalesced, cultural pride began to be increasingly expressed through music.

The advent of commercial recordings by and for African Americans can be dated to Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920, an unprecedented commercial success. The music recording industry’s marketing category “race records” was established to identify this market, the term borrowed from the African American vernacular use of “race man” during that era to express racial pride and solidarity. The music industry used “race records” as a catch-all category for most forms of African American music including jazz, blues, and religious music, and—following Mamie Smith’s success—produced recordings by Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Ida Cox, Alberta Hunter, and other female vocalists in a similar blues style with the musical accompaniment of piano, horns, wind instruments, banjo, and percussion.

Some recordings in the “race records” category included genres that would become foundations for R&B, in particular blues, big band, and gospel. The blues piano and guitar duo Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell, with Carr’s smooth vocals in the hit song “How Long, How Long Blues,” later would influence R&B artists such as Charles Brown and Ray Charles. In Chicago, boogie-woogie piano players Jimmy Yancey, Clarence “Pine Top” Smith, and other pianists developed the rolling bass lines that would influence R&B pianists such as Amos Milburn.

Hear “African American Gospel Music,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

Pianist and composer Thomas A. Dorsey’s composition “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” now a standard, is considered a touchstone in the emergence of gospel. Working in Chicago with vocalist Sallie Martin, Dorsey crafted gospel by blending musical elements from blues into sacred song forms. By the end of the 1930s, swing bands like Chick Webb’s influenced artists such as Louis Jordan, who incorporated swing horn riffs into the jump blues.

The Second Migration and Rhythm and Blues

The early development of R&B occurred in tandem with the second migration of African Americans who moved from the Southern and rural regions of the United States during and after World War II. Between 1941 and 1950, the African American population of Western cities grew by 33 percent, with about 340,000 African Americans from such states as Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma settling in Southern California for employment in the region’s expanded defense industries. Similar patterns of migration took place in the Midwest to Chicago and Detroit, and in the East to New York City.

These expanding African American urban communities with increased economic resources presented a large audience hungry for social interaction with music and entertainment. Within these racially segregated communities, cross-generational groups of musicians and performing artists provided musical affirmation for these populations. The surge in L.A.’s African American population, for example, gave rise to a vibrant entertainment scene extending along Central Avenue that by decade’s end would support no less than eight record labels specializing in R&B.

Hear “Rhythm & Blues,” a Smithsonian Folkways playlist

One important stylistic prototype in the development of R&B was jump blues, pioneered by Louis Jordan, with his group Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five. Originally from Arkansas, Jordan was a former member of Chick Webb’s swing band that had dominated New York City’s Savoy Ballroom through the 1930s, after which he moved to L.A., finding success there both as a musician and in films. Jordan’s group, a combo ranging in number from six to seven musicians, consisted of three horns and a rhythm section, while stylistically his music melded elements of swing and blues, incorporating the shuffle rhythm , boogie-woogie bass lines, and short horn patterns or riffs. The songs featured the use of African American vernacular language, humor, and vocal call-and-response sections between Jordan and the band. Jordan’s music appealed to both African American and white audiences, and he had broad success with hit songs like “Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby” (1944).

Southern musicians, especially performers from Texas who had moved to Los Angeles, were no less influential on the development of R&B. Pianist Charles Brown, first with Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers, developed a smooth blues and R&B sound in post-war Southern California. Noted for his crooning vocals in the style of Nat King Cole, Brown had great success with mellow blues songs like “Drifting Blues” (1945) that would go on to influence fellow Texan Ivory Joe Hunter and Ray Charles.

Texas-born blues guitarist T-Bone Walker, who worked with jazz bands in South Central L.A. clubs, pioneered the use of the electric guitar and developed a single-line soloing style based on jazz horn lines that continues to influence musicians today. His 1947 song “Call It Stormy Monday,” based on a harmonically extended twelve-bar blues form, with lyrics referencing the working-class life, has become an R&B and blues standard. Boogie-woogie pianist Amos Milburn from Houston-a popular performer in clubs around L.A. ‘s Central Avenue-whose recordings on the independent Aladdin Records were based firmly in the blues and boogie-woogie style as performed in Texas, appealed to audiences on the West Coast and beyond with hit songs such as “Chicken Shack Boogie” (1948).

Jerry “Swamp Dogg” Williams performs “Crawdad Hole” at the 2011 Folklife Festival. Filmed by Eric Griffis, David Barnes, and Holden Young; edited by Michael Headley

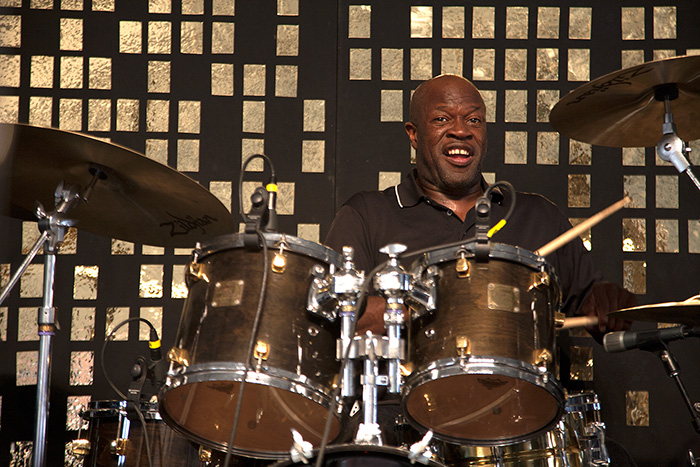

Throughout its history, the sounds that have come to define R&B have derived from a range of musical characteristics, instrumentation, and ensembles, ranging in size from tight piano trios to large groups with full rhythm and horn sections. Performed with a core of acoustic instruments in the 1940s, R&B was “plugged in” and electric from the late 1950s forward.

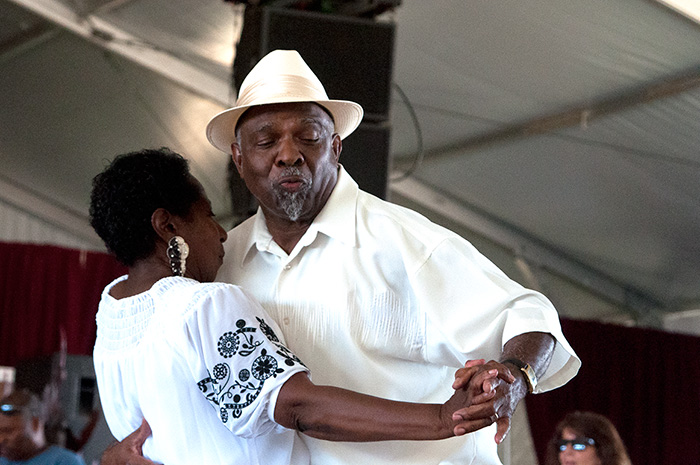

Rhythmically, R&B now encompasses a wide breadth from blues shuffles with a back beat to boogie-woogie, modified rumba rhythms, and syncopated variations of eight-beat rhythm patterns that are the hallmark of rock ’n’ roll, and more. Even slow R&B ballads feature a palpable rhythmic pulse, while up-tempo songs might include polyrhythmic arrangements to create rhythmic density. At its core R&B is dance music that compels the listener to respond. It is the creative melding and mixing of antecedent song forms-including blues, gospel, swing, and other harmonic structures-with new innovations that keep the evolving sounds of R&B contemporary.

A Wider World

While R&B music was not explicitly political from the late 1940s through the 1950s, its appeal across racial divides served as an emotion and psychological bond that linked American youth of all races and ethnic backgrounds. By the late 1950s, social and cultural changes were occurring that set the stage for the coalescence of civil rights activism and ethnic consciousness in the decade to come.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, founded in 1957, employed a strategy of non-violent mass resistance and demonstrations under the leadership of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. to challenge the injustices of long-sanctioned racial segregation. In 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee joined in the struggle to secure voting rights and break down the social and economic barriers of segregation throughout the South. The Black Nationalist agenda of Malcolm X presented a counter-strategy to non-violence in response to racial injustice, and gave rise to the Black Panther Party. And with the growing opposition to the Vietnam War, it became clear that political sentiments within African American communities were in transition.

As these events in the civil rights movement focused America’s attention on the moral contradictions and social inequity within society, R&B artists and songwriters increasingly began to address issues that went beyond interpersonal relations and group camaraderie. The release of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” (1964) was in the advent of politicized R&B music. It was followed by songs that overtly related to the civil rights, ethnic consciousness, and anti-war movements. Curtis Mayfield’s “Keep on Pushing” (1964), James Brown’s “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud” (1968), and Marvin Gaye’s seminal album “What’s Going On” (1971) all directly addressed civil rights and social issues and enjoyed great market success.

As R&B in this period was associated increasingly with the civil rights movement, record executives at both Motown and Stax would produce artists and undertake initiatives that explicitly reflected their commitment to African American community empowerment. In 1968, for example, Stax signed the Staple Singers, whose music grew out of performances in Chicago-area churches and enjoyed crossover gospel-to-R&B success with their “protest” and message-oriented repertoire. Patriarch Roebuck “Pops” Staples had reportedly steered his family in this direction after hearing Martin Luther King Jr. speak, telling them, “If he can preach it, we can sing it.” In 1970 Motown launched its spoken word Black Forum label featuring Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, and others. In 1972 Stax artists participated at an event in South Los Angeles, Wattstax, from which the proceeds were donated to local African American community causes.

In 1971 Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff founded Philadelphia International Records (PIR), a company whose music explicitly celebrated African American identity and consciousness. Through songs such as “Only the Strong Survive,” “Wake Up Everybody,” and “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now,” and their slogan “there’s a message in the music,” PIR reminded listeners to be aware of the struggles of the past and those yet to come.

Conclusion

For the first five months of 1967, a romantic ballad—“Tell It Like It Is,” passionately sung by Aaron Neville—climbed to the number one spot on the U.S. R&B charts. Released in November 1966, just a month after Stokely Carmichael delivered his now-famous “Black Power” speech in Berkeley, the song stayed high in the charts through May 1967, while the Supreme Court was deliberating its landmark decision in Loving v. Virginia on the constitutionality of anti-miscegenation legislation. Essentially a love song, it did not comment upon any of the roiling civil rights issues of the time—neither the urban riots, nor the persistence of segregation, legal and de facto. But in 1970, the phrase “tell it like it is” was appropriated by Stax Records as the slogan for its spoken-word Respect label. The catalog consisted of readings and recitations reflecting black consciousness, and their intended audiences were school systems and churches.

The popularity of the song and its subsequent adaptation and reinterpretation by artists from Otis Redding to Andy Williams to Freddy Fender, the Dirty Dozen Band, and Heart, tell us how the music that speaks about a history of marginalization and exclusion also tells a story about resilience and resistance. The song had such broad resonance that it ultimately played a central role in shaping mainstream American popular music.

Two 2011 Folklife Festival programs come together, demonstrating that genres are ever-evolving: The Monitors from Rhythm and Blues and Chirimía La Contundencia from Colombia: The Nature of Culture. Filmed by Gary Francis; edited by Rafadi Hakim

Mark Puryear was the curator for the 2011 Folklife Festival program Rhythm & Blues: Tell It Like It Is. He holds an M.A. in ethnomusicology from the University of Maryland, College Park.